TAKES: Is it okay to trace?

Renton Hawkey's 100% foolproof and totally honest method to justify tracing!

Hey fellas — today I want to talk about a perennial discourse.

No, it’s not the latest culture war melee. We’re taking a break from that and debating something much more procedural. Nonetheless, today’s topic emerges every now and again, in the same way, to tie us into knots.

And that topic is, whether or not it’s okay to trace for your art.

Big reminder folks that if you like this post, hit the ❤️ up there to let me know, or leave me a 💬 down below, I’d love to hear from you.

SO, to trace or not to trace?

It’s one of those things that sounds like a no-brainer. “Tracing is cheating, and gives a false impression of an artist’s actual ability. Tracing is wrong.”

But how it shakes out is a little more complicated than that. For starters, what counts as tracing?

There are mainstream comic artists that trace outlines of buildings from photographs they took. Is that cheating?

There are mainstream comics artists that rip panels from other artists, and sometimes themselves. Is that cheating?

There’s at least one mainstream artist who screencaps ladies getting ploughed on PornHub and traces those. Sounds fun, but again! Is that cheating?

Probably at least one of these examples is a little gray for you. It’s complicated! Thus, there are folks in the community who think tracing is perfectly defensible and acceptable as a tool in the artist’s toolkit.

After all, deadlines are murder, and making comics is time-consuming. Borrowing a background here and there or tracing a skyscraper for a quick establishing shot doesn’t change the fact that overall, you still largely created an original work of art.

And even if you had to trace here and there, your linework, your lighting scheme, whatever else you threw into the panel, like smoke or bystanders, that’s all original art. That’s all something only you can do. The thing you traced is a small part of a greater whole; you still made it your own.

But there are some examples of tracing that even cause the practice’s defenders to grind their teeth. There are comics artists who trace first-result Google photos, or pull a musician’s face from a famous album cover everyone knows at a glance. You might look the other way on a little bit of tracing here and there to get an artist out of a jam, but there are some artists who just clearly rely on tracing too much and too often.

There are also indie artists who justify tracing to compensate for a lack of technical skill. There’s a problem with this approach that almost everyone can understand — this method doesn’t really help you actually improve your technical skills. It can be seen as a necessary evil that eventually you evolve out of, but it ends up being a crutch that enforces bad habits and can inhibit real growth.

These last 500 words or so hardly exhaust the scope or history of the discourse on the morality of tracing in comics. All I wanted to do there was to shake up your moral reaction to the idea of tracing, because most people do have an initial knee-jerk instinct about it. It’s either not that big a deal, or completely verboten.

My take? You guessed it. It’s complicated.

As a young pup, I fell squarely into the “tracing is always cheating” camp, and indeed, there are versions of the practice that I do think qualify as “cheating” to this day.

But the more examples I was exposed to, and the more I saw artists I respect admitting to tracing here and there, the more nuance crept in to ruin my comfy absolutism.

The truth is this: Tracing, for better or worse, is ubiquitous in comics, and always has been.

Where to draw the line on your tolerance for it is something only you can decide. In the rest of the newsletter, I’ll tell you where I draw mine. I’ll also offer an example from my own work to show how tracing sometimes works its way into my process. And you can decide whether you think I’m right or wrong.

My two cents on tracing

Before jumping into an example, let me enumerate where I stand on the issue. Feel free to skip to the next section if you want to dive into the process stuff.

Artists should focus on improving their technical skills

If an artist has to trace because they lack a technical skill, then I think they should make it their goal to work on the technical skill they are lacking so that next time, they don’t have to rely on tracing to pull off a similar panel.

This is to say that tracing might save you in a pinch, this time, but it’s not an ideal solution. Use it as a way to identify your technical weaknesses and then work on improving those weaknesses for next time.

But don’t let it become a crutch. Challenge yourself to continuously improve your technical skills so you rely on tracing less and less (and tracing isn’t going to help you improve those skills; you’re going to have to learn them the hard way!).

Traced art doesn’t often translate into good comic art

A lot of newbie artists can fall into a trap of over-relying on photo reference. Photo reference is a valuable tool for artists, but mostly for teasing out the particular details of an item like a fire hydrant, to get a quick sense of depth or space between objects in a big shot, or to tease out a nuance of human expression.

But the rookie trap (and one I fell into myself) is trying to draw a photo reference line for line — to capture realism.

And you know the problem when you see the finished product. It’s stiff, and it lacks dynamism. There’s no cartooning.

This is because photography and comic book art are completely different mediums of art. A great photograph doesn’t make a great comic panel.

Comic art is about hyper-realism. It’s about angles and drama and composition. It’s almost dreamlike. The better you get as a comic artist, the more you notice the cartooning and reality-bending that you never noticed as a reader.

As you’re becoming an artist, the best way to use photo reference is just that — as reference.

It’s better to study the greats in our industry and figure out how they translated something like the Empire State Building to the comic page. Look at great pages and ask yourself what the artist had to move around, or make hyper-real, to make it make sense. Honestly, try to imagine how comic panels would look as photographs, and you’ll figure out pretty quickly how ridiculous it would probably look — how staged and awkward and forced it would end up being.

This was a bit of a tangent, but you can probably see where I’m going with this — If losing cartooning is a problem with merely using photos as a reference, it’s a problem made ten times worse by actually tracing a photo. You’re running the risk of making your art as rigid and wooden as it can get!

Even great artists who trace here and there know that they need to fudge and tweak and cartoon the panel to make it a comic. If you just trace a background you found on Google and go “that’s that,” it’s going to read false.

However…

Tracing can be done honestly

Artists who trace often aren’t doing so to cover up a lack of technical ability. They’re tracing for “filler.”

Sometimes it’s easier to trace a building edifice that isn’t the focus of a splash page, because it’s just a background element and you don’t want to spend the time creating a perfect grid when you can just find a building and loosely sketch in the windows.

Sometimes artists steal a silhouette from Will Eisner because, frankly, Will did it the best. And those artists, when called out, will admit it proudly. Steal from the best!

Overall it’s a question of honesty, and honesty with yourself. Don’t use tracing to mask a lack of technical skills. If people find out you traced the Empire State Building once to save time, I think they’ll forgive you. If they start to figure out that you just can’t draw hands, or work with 2-point perspective, or whatever, then it’s going to seem more dishonest, like you’re trying to get away with something.

Now, all of this is fairly easy to say from a 10,000-foot distance. Let me lay my own cards on the table and show you exactly how tracing sometimes factors into my own work.

The Renton Hawkey Method: Reference Tracing

Here’s where tracing factors into my work from time to time in what I think is, at least for me, a totally ethical and justifiable way.

I call it “reference tracing.”

This method is much more about making sure my art is on the right track than capturing realism. You might not think this qualifies as tracing at all! But I think there’s a specific point at which it does qualify.

It’s not something I do very often. But every once in a while, especially if I’m drawing something I don’t have a lot of experience drawing, it can come in handy.

Let’s walk you through it. Take the recent pinup of Eva from Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater you saw in a previous issue of rent*space.

I don’t draw motorcycles very often. This is actually probably my first time ever drawing a vintage Triumph Bonneville.

So, I did some Googling with the express purpose of finding a bike I could use for reference, both in terms of detail and the angle I’d be looking at it from.

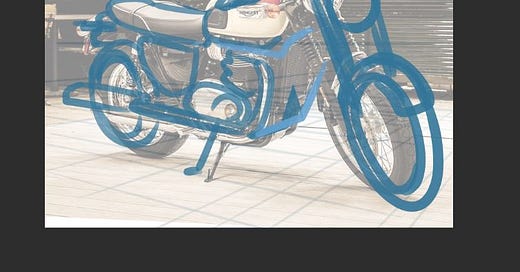

In the image below, we have a horizon line right about at the headlight, meaning the photographer is probably on their knee, or sitting.

Since I knew Eva would be curled up cat-like on the bike as the main point of focus, this is the perfect angle.

With the photo in-hand, I set about creating a grid in Clip Studio Paint. Once I got my “environment” grid, I created another 2-point grid at an angle to mimic the parked bike (since the bike rests at an angle to the environment — again, knowing the technical stuff is important).

Once that was set up, I started drawing some rough boxes to “frame” the eventual motorcycle.

At this point, I’m completely eyeballing it. I’m thinking about the horizon line, where Eva is going to be, the overall composition, and am really just working on getting a very rough motorcycle in there for placement on items like the wheels, the handlebar, etc.

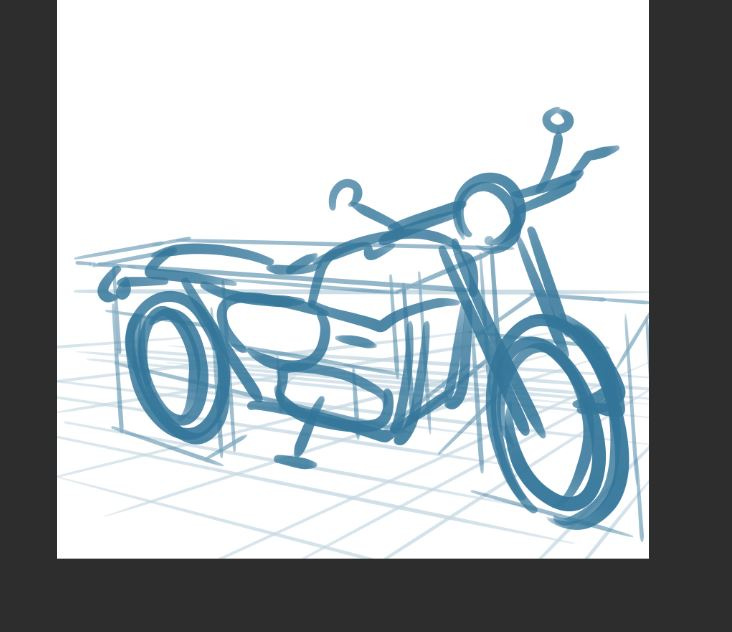

Once that part was done, I removed my grids, and looking at the motorcycle in a separate window, I set about drawing an extremely rough bike:

Not too bad! I probably could have moved forward with this as-is, and if it was a comic panel, I probably would have.

But for prints, where the thing you draw is the only thing the viewer is looking at, you have to do a little better. In a comic, a reader might not necessarily stop and study every detail, because the “whole” they are taking in is the story.

Not so with a print — the “whole” is the single drawing, so I like to be a little more on the money.

And here’s where the question of tracing comes in.

Up until this point, the photo reference was in a different panel. Now, I move the photo into a layer underneath the rough drawing itself, and drop the transparency to about 50%.

The good news is, I was pretty close with my rough sketch!

But the overall height of the bike is a little off. The wheels are a bit small, and the handlebars are a little too low.

From here, I don’t scrap what I’ve done and trace the actual bike, because again, it needs to be cartoony and not photo-real. But for scale and space and everything else, It does make sense to do some rearranging with the wand.

So that’s what I do:

I perked the seat up a little bit, changed the front tire and handlebar, and moved a couple things to be a little more “anatomically precise.” Then, I re-drew a new rough over top of the messy wand layer.

You should notice here that it’s still not a perfect trace of the source image. That’s intentional. I’m modifying this on purpose, tweaking the nipple of reality and cheating the art some to make the pose and composition work the way I want it to. Remember what I said about hyper-realism.

Pushing the handlebars out further gave me a little more room for the slinky figure, and keeping the back wheel smaller makes the angle a little more dramatic overall, so these are good choices for a drawing that technically don’t map onto real life perfectly.

Again, this is the key to using photo as a reference, not the Word of God.

Anyway, now it’s time to delete the reference photo layer and draw my loose figure on top.

This is usually the point in my art where I’ll give it a good “squint” test and have a few other people look at it to make sure nothing pops as weird or phony.

Once it passes all those tests, I’ll do a super rough pencil:

And from there, the finer detail work in the inks, the colors, and everything else:

Questions, comments, concerns, complaints?

So, what do you think?

Is this tracing?

Is it cheating?

Does it change your appreciation of the art at all?

Does it make any difference to your enjoyment of it?

What’s fair game when it comes to tracing in comics? What isn’t?

I’d love to hear your take.